SPECIAL REPORT: Displaced By Terrorists, Abandoned By Government, Children In Niger State Face Bleak Future

Awodo Sale is only 8 years and had just started attending a primary school in a community near Kaure, his hometown in Shiroro Local Government of Niger State until Boko Haram terrorists sacked the community in 2019 and hoisted their flag. His parents were among residents who managed to escape the brutality of the terrorists and fled to Gwada, where the state government established a camp for displaced persons.

Sale is among the 2,011 children now living as refugees in the camp with no access to any form of education. There are no schools to accommodate all the displaced children as primary school classrooms had been converted to hostels to accommodate IDPs.

Advertisement

Records at the Gwada camp, which is one of the two biggest camps in the state, showed that only 32 children currently attend school due to lack of space.

But Sale, like thousands of other children, is not lucky to be among the 32 child refugees currently going to school in the state. Instead, he and others are being used by their parents to earn income to enable them to feed and afford basic necessities, having been abandoned by their state and local governments.

The eight-year-old looked distraught and lost in his dirty and torn clothes when THE WHISTLER met him at the camp.

Advertisement

“If I wake up I go to work or farm because I’m not going to school like other children,” he said in his Gwari dialect, pointing at the school nearby. “But if there’s no work or farm I will be at home. If I have a sponsor I will like to go back to school.”

But Sale may never have the opportunity to go back to school and acquire western education. He seemed condemned to join the growing number of out-of-school children in the state as terrorists continue their advance and carve more territories in the state and other parts of the north.

The latest official figure from the State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB) shows that a total of 513,689 children were out of school in the state as of 2018. That figure must have gone further up since 2019 when terrorists entered the state.

Children in the IDP camps in the state, as young as 6 years, engage in farming for survival. Others sell edibles made by their parents during the day. The female children are quickly married off to escape the dreary life at the camps.

Parents’ Burden

Advertisement

Mary, a 65-year-old widow whose husband was killed by terrorists who invaded Kaure in 2019, sat on the concrete floor of a classroom turned dormitory for refugees at the Gwada camp, dejected. She seemed to wear her worries on her face, which accentuated the gloom on her wrinkled face.

She struggled to recall what brought her to the IDP camp from her ancestral home of Kaure—a farming community in Shiroro. The community is now under terrorists’ control and she seemed to push back tears as she recollected what happened.

Her husband was killed in April 2019 when terrorists attacked their farmland, demanded and carted away food produce, razed houses, and killed many, causing them to flee. Other residents also fled. The terrorists subsequently hoisted the Boko Haram flag in Kaure.

Over 2,800 residents from several communities, majorly from Madaka, Masuku and Zongoro were similarly displaced by the terrorists. They all found some refuge in the peaceful town of Gwada, where the state government established an IDP camp for persons fleeing from terrorists.

But the Gwada IDP camp is one of the major temporary settlements for displaced persons in the state. It shares space with a government-owned primary school. There is another camp at Kuta, a town under the same local government, where the headquarters is located. Kuta is about 45 minutes drive from Gwada. The camp occupies nearly 80 percent of the learning facilities at the Day Secondary School TumTum, Kuta.

Advertisement

IDP Camps Stink

No less than 30 persons are made to live in a classroom space at the camps, in cramped conditions. THE WHISTLER noticed insufficient mattresses with some “rooms” having less than 10 mattresses. The rest have to sleep on mats or spread their own clothes on the floor.

The sanitary conditions of the camps were unhygienic as residents use pit latrines that were hurriedly dug within the compounds. There were flies all around the camp, obviously attracted by stale feces that were noticeable to visitors to the camps.

There was no source of potable water at the camps until a Non-Governmental Organisation, DIWA, came to their rescue by providing a borehole each at Gwada and Kuta camps.

Most of the refugees have nothing to do; many have yet to recover from the trauma of fleeing from their homes and farms, and being unable to start a new life.

But a few, like Bala Pada, who also fled from Kaure, is able to go out to do farm work for others to earn money. He is now one of the leaders of the refugees at the Gwada camp. He said, “We hustle to feed by ourselves mainly through the farm labour we engaged in. My wife and children follow me to work for people”.

The father of seven children disclosed that over 1,000 residents of Kaure were displaced and are currently taking refuge in other camps within and outside the state.

IDPs Pick Their Medical Bills

Findings by THE WHISTLER revealed that when people are sick, they have to take care of their own hospital expenses as there are no medical facilities at the camps. The IDPs have to go to hospitals within Gwada or Kuta to access treatment. Though the camps have dispensaries, they are hardly stocked.

“It is the menial jobs that we do that give us little money to eat and go to the hospital. When our children are sick, sometimes the government used to send drugs for us, but they are not enough,” Pada said.

Sick refugees told this website that it’s a struggle to get medication when there is no money.

Among those who could not afford the hospital is Halima Salisu from Masuka village. Her baby was just a month old when THE WHISTLER spoke to her at Kuta camp.

Covered in her red hijab, the new mum had given birth in the camp with the help of an external nurse. While still carrying the pregnancy, it was difficult for her to meet up with anti-natal appointments regularly due to the cost. She usually went to dig for gold (illegal gold mining) along with others to survive.

Her one-month-old baby was yet to receive the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination, and that of Hepatitis B Birth dose.

“The child has not been immunized,” she said, expressing no hope for immunization in the nearest future.

For other women at the camps, it is a similar story of lack and labour as some of them continue to give birth and increase the number of out-of-children.

The State Government Is Helpless

Yusuf Bala, the Desk Officer at Kuta camp told THE WHISTLER there was only a little the authorities could do due to the overwhelming number of displaced persons seeking refuge in the state.

Although there are only two major camps in the state, Bala said five other satellite camps exist across the local government due to the lack of space to accommodate them.

He identified the camps as located in Gurmana, Kwateu, Gijiwa, Erena, Galkogo, and Zumba. But all the camps depend on what comes from Kuta camp.

Records made available to THE WHISTLER at the Kuta camp showed that a total of 2,813 people were displaced as of December last year. The figure was collated from 71 communities affected by terror activities.

A breakdown of the figure given to the website shows that children constitute the major victims of terrorism in the state. A total of 2,011 children were displaced while 722 women and 80 men were affected.

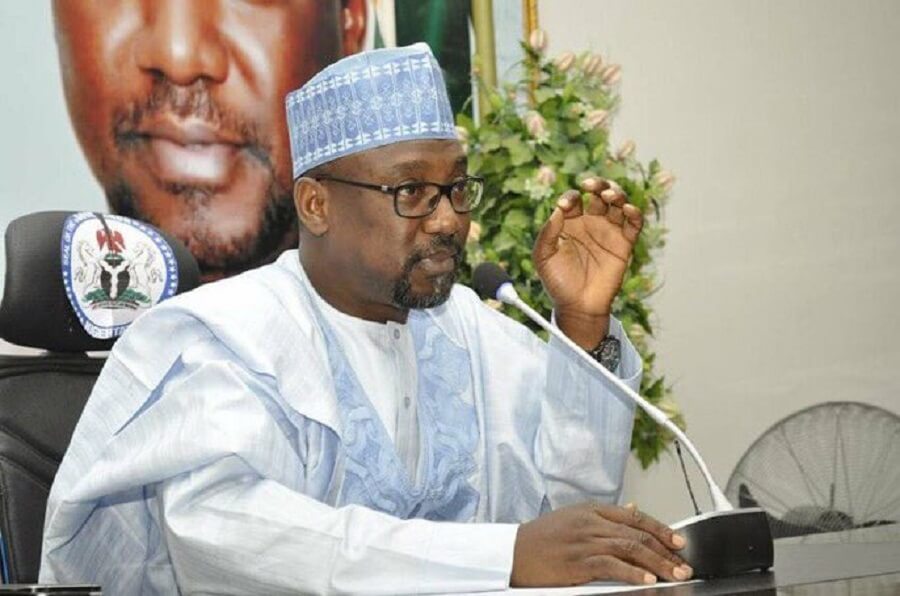

Governor Abubakar Sani Bello has stated that the issue of out-of-school children could not be addressed until terrorists are defeated. He also said the state government was helpless against terrorists without federal government’s support.

The hope of out-of–school children in the state for good education may continue to be a dream for years to come. Perhaps, the young Sale already knew he would not be like those children he sees in uniform marching to school.

“I want to be like them,” he said while looking into the eyes of the reporter for confirmation of his dream.