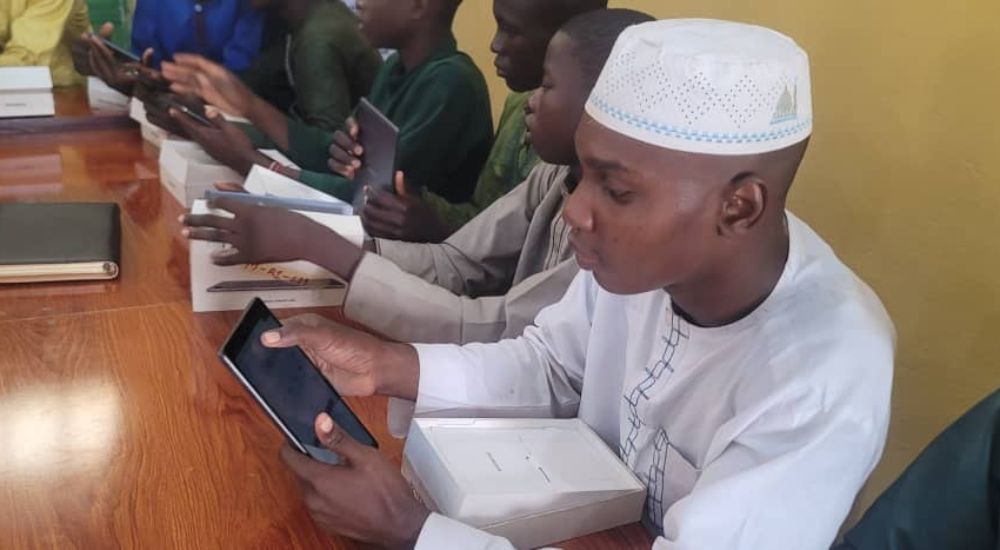

At a modest training hall in Sultan Muhammadu Maccido Institute in Sokoto, northern Nigeria, 18-year-old Sadi Muhammad leans over a smart tablet. A smile creeps across his face as he proudly announces in

Hausa, “Look, I can type my name.”

Only months ago, Sadi was an Almajiri child, part of the millions of Nigerian youth moving between informal Qur’anic schools and street life, caught in the undertow of poverty, displacement, and educational exclusion.

Today, he is part of a bold experiment, the Sokoto Digital Village, a pioneering project teaching computer literacy, coding, and digital design to out-of-school children in the Hausa language.

What seems like a simple language issue in learning is actually a powerful political statement. It reflects a growing global awareness that language is central to digital inclusion. Until technology speaks the world’s many mother tongues, its benefits will remain out of reach for billions.

Digital Village

The Sokoto Digital Village is a UNICEF-backed pilot programme that targets vulnerable young people, aged 14 to 22, from Almajiri boys and out-of-school girls, to reduce digital exclusion and unemployment.

Advertisement

The first cohort comprises 150 boys and 100 girls, drawn from children without family support and adolescent girls who have either dropped out or never had access to formal education

According to a UNICEF official, the participants receive digital literacy training four days a week (Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday), while weekends are dedicated to vocational skills training.

“Available trades include tailoring, knitting, bakery and catering, carpentry, plumbing, and shoemaking.”

“This first phase is a pilot designed to run for one year, so we can understand the challenges, especially during farming and fasting seasons when attendance drops. Subsequent cohorts may last six to seven months based on lessons learnt.”

He said that the selection was based on a UNICEF survey identifying children who are out of family care and girls not currently enrolled in school.

Advertisement

On sustainability, the official said that the Sokoto State Government is a key partner, with facilitators drawn from government agencies to ensure continuity beyond the pilot phase.

The Language of Inclusion

Across Nigeria and much of the Global South, the digital divide is not just about hardware and connectivity. It is linguistic, cultural, and systemic.

Hamisu Isa, a digital rights expert with H&E Consults, said that the assumption that English should be the default language of tech education and digital tools has excluded millions of learners who lack fluency in colonial or dominant languages.

Nigeria has over 10 million out-of-school children, many of whom face educational barriers rooted not only in poverty or gender but in language mismatch. “We realised that many Almajiri children and out-of-school girls cannot follow ICT classes in English, but by integrating Hausa, we are removing the first barrier,” said the UNICEF official.

Advertisement

He mentioned that the early results are powerful, with high attendance and low dropout rates. Students like 16-year-old Karibu Shu’aibu are discovering new identities.

“I used to be afraid because I could not speak English, but when the teacher explained graphic design in Hausa, I understood. Now I can design flyers and dream of running my own business.”

New Lens on Tech Accountability And The Global Movement for Local-Language

Sokoto’s experiment poses tough questions for global technology ecosystems and AI developers. As powerful technologies like artificial intelligence, large language models, and digital education tools shape the future, who is building them, and for whom?

Ibrahim Zubairu, a tech expert and the founder of Malamiromba, said that the overwhelming majority of AI systems, including those used in education, job markets, and governance, are trained on English-language data and cater to English-speaking users.

According to him, this creates systemic biases, where non-English speakers are either excluded, poorly represented, or misunderstood.

He said tech accountability takes on new meaning, “not just about algorithmic bias, surveillance, or misinformation but about language justice.” If AI tools cannot understand or interact in Hausa, Yoruba, Zulu, or Quechua, are they serving humanity or only a sliver of it?”

“When you teach coding in local languages, children realise technology is not foreign. We have seen boys who never attended formal school create simple mobile apps. They don’t just use tech; they own it.”

He said the digital village is not an anomaly but rather part of a global trend toward decolonising technology and promoting linguistic inclusion in AI and education.

Across Africa, organisations like Masakhane are building open-source AI models in Swahili, Igbo, Amharic, and dozens of under-represented languages.

Zubairu said that in countries like India, edtech startups are translating STEM content into Tamil, Bengali, and Marathi to reach rural students. While in Latin America, Indigenous communities are demanding digital tools that respect and incorporate their languages and worldviews.

“These efforts reflect a growing consensus that language matters deeply. Not only for better comprehension, but for cultural identity, social inclusion, and self-determination in the digital age,” he added.

Yet most global tech companies still operate on extractive models, building tools in Silicon Valley and shipping them globally, with little regard for local contexts. The result, according to experts, is “a digital world that mirrors and magnifies the inequalities of the real one”.

Breaking the Cycle of Digital Exclusion

Language is often overlooked in digital policy conversations, but it is a fundamental axis of exclusion, said Isa. According to him, in the northwestern states, tech was once seen as something alien and available only to the urban elite, those who spoke English, or those who could afford devices.

“ But by teaching digital skills in Hausa, the Digital Village is rewriting that narrative”.

Nura Shehu, a tutor at the Digital Village, said that the centre uses a specially designed Learning Management System (LMS) known as ilimi digital, which provides tailored curriculum content for the beneficiaries.

“To bridge the literacy gap, we adopt interactive methods such as demonstrations and examples, while teaching is conducted primarily in Hausa to ensure effective communication.”

He said that with the use of digital tablets, internet access, and lessons delivered in languages the beneficiaries understand, the learners are now able to overcome language barriers, resulting in boosted digital literacy and self-learning.

“Digital inclusion is not about handing out gadgets. It is about ensuring every child, no matter their background or language, can see themselves in the future of technology.”

Isa sees the Digital Village as a blueprint for a more accountable and inclusive tech future, one where AI and digital tools are not just translated but designed for and by diverse language communities.

He outlined several demands calling for changes in tech practices that will promote greater accountability.

According to him, AI developers must invest in low-resource language models and multilingual datasets.

“Tech companies must build user interfaces and educational tools that support indigenous and local languages; governments and NGOs should prioritise language inclusion in their digital literacy programs and tech policies.”

“Also, funders and global institutions must recognise that true digital inclusion begins not with infrastructure, but with comprehension, context, and culture.”

The Future, in Their Own Words

Back in Sokoto, children like Karibu no longer see computers as symbols of exclusion. “I want to own a computer so that when I go back to my village, I can teach my friends,” he said proudly. And Fatima, who had never stepped inside a classroom before, now aspires to become a tech entrepreneur.

For these youths, the opportunity to learn tech in their local languages is not just a technical milestone but a statement of belonging, a signal that the future includes them, in their own language and on their own terms.

“If global tech is to be truly accountable, it must follow their lead. It must begin not with dominance but with dialogue that speaks the language of equity in every mother tongue,” Zubairu concluded.

– This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate