Sokoto’s School Revamp, Winning Back Out-Of-School Children

For years, classrooms in Sarkin Baura Model Lizzamiya primary school Dange Shuni, stood as a reflection of Nigeria’s education crisis with broken desks, leaking roofs, and cracked walls that silently told the story of a forgotten generation.

But today, that same school paints a new picture, one of revival and renewed promise as Sokoto State government intensifies efforts to reclaim the future of its children.

Once branded as the state with the highest number of out-of-school children in Nigeria, Sokoto is now rewriting its story through strategic investments and community-driven reforms.

According to a 2022 UNICEF report, an estimated 1.2 million children in Sokoto were out of school, a staggering figure that triggered concern and urgency among government officials, traditional leaders, and education stakeholders.

Aminu Magaji, a farmer and father said that his decision to withdraw his son from school was born out of frustration, not choice.

Advertisement

“My son always came back home looking very dirty,” he recalled. “During the rainy season, he returned with a soaked uniform and wet books. He told me the roof of their classroom was leaking, and there was no place to hide from the rain. That was the day I stopped him from going to school.”

His experience mirrors that of countless parents across rural Sokoto, where dilapidated schools, overcrowded classrooms, and lack of basic learning materials have long discouraged enrollment.

“When the environment is not conducive, learning cannot take place, Magaji added. “A school should be a safe haven for children, not a place they dread.”

GOVERNMENT STEPS UP

Confronted with these grim realities, the Sokoto State Government under Governor Ahmed Aliyu has intensified efforts to reverse the trend. Recognizing that poor infrastructure was a major barrier, the administration launched a comprehensive school renovation programme across the 23 local government areas.

Advertisement

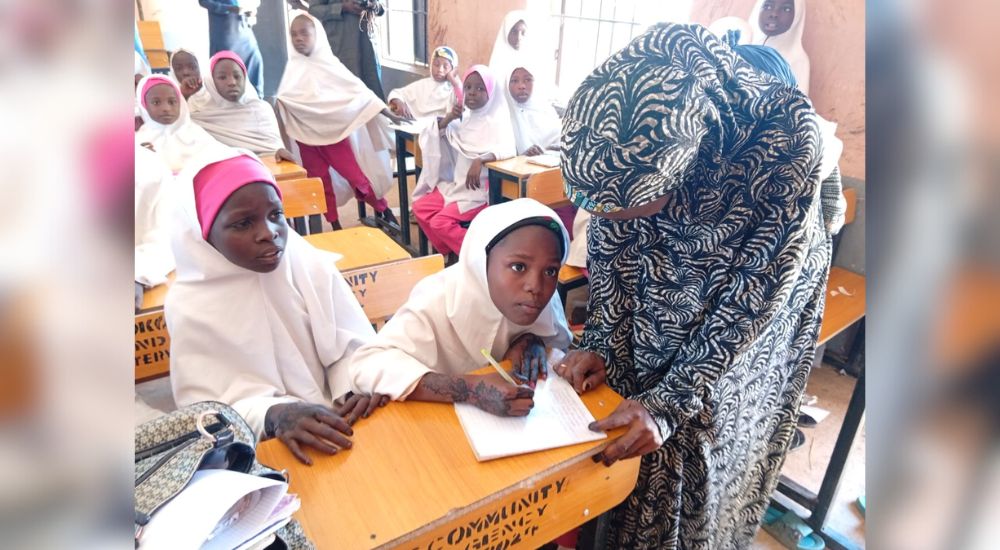

One of the early beneficiaries is Sarkin Baura Model Lizzamiya primary school. Once a symbol of neglect, now transformed into a model of what the new Sokoto vision for education looks like.

“We used to have pupils sitting on the bare floor, but now, not a single child sits without a desk. Our classrooms are roofed, ventilated, and furnished, said Bello Abubakar Dange, the school’s headmaster.

He said that enrollment has increased by over 70 percent compared to the years before the renovation.

He attributes this improvement not just to the physical facelift but also to a renewed sense of trust from parents. “Once parents saw that the school environment is safe and clean, they began sending their children back. That is how confidence is built.”

TEACHERS FINDING PURPOSE AGAIN

For Aishat Ahmed, a 27-year-old social studies teacher at the same school, the transformation runs deeper than infrastructure. A mother of two and a former pupil of the school herself, Aishatu says the new facilities have reignited her passion for teaching.

Advertisement

“I am a mother, a wife, and a teacher and I once sat in these same classrooms as a little girl,” she said with a smile. “My dream is to see every girl in Dange Shuni educated.

She said the renovation has made teaching easier, and the children are more excited to come to school every morning.

According to her, the provision of free learning materials such as textbooks, notebooks, and writing tools by the state government has further eased the burden on parents. “Many of our pupils now have access to books for the first time. That alone is a motivation.”

BEYOND RENOVATION: TACKLING THE ROOTS

While the school rehabilitation programme remains a cornerstone of the government’s effort, it is only part of a larger strategy aimed at tackling the roots of the out-of-school crisis, said Professor Mustapha Tukur Namakka.

In an interview, Professor Namakka, who is the Executive Secretary of the Sokoto State Female Education Board, explained that the government has established a high-powered committee under his supervision to address the problem comprehensively.

He said that the committee is mandated to identify and re-enroll out-of-school children through community-based sensitization and targeted interventions.

According to him, the committee recently conducted a two-day stakeholder engagement with 87 district heads across the state to secure their commitment to the exercise.

“Also, the training of Quality Assurance Officers and other field officers will soon commence in all 23 local government areas as part of preparations for a state-wide mapping exercise,” he added.

The state is also adopting a new, evidence-based data mapping approach to identify and capture every school-aged child into a centralized database with a tracking system. “Enrollment, retention, and completion of each child will be monitored using an individual identification code,” Professor Namakka explained.

He added that the government is working closely with traditional rulers, religious leaders, and civil society organizations to make education a shared responsibility.

“Education is the foundation for development, and Governor Ahmed Aliyu’s administration is fully committed to ensuring that no child is left behind”

BRIDGING THE GENDER GAP

While gender disparity is also a challenge rooted in cultural beliefs and early marriage practices, the state government has introduced conditional incentives to encourage parents to send their daughters to school. These include scholarships, free uniforms, and feeding programmes designed to ease the economic burden on families.

Community-based learning centres have also been established in hard-to-reach areas, bringing education closer to children who previously had no access to formal schooling, said Sambo Ahmadu, a community leader in Sokoto.

He said that the Sokoto state renewed education drive has also attracted strong support from development partners such as UNICEF, the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC), and the World Bank’s Better Education Service Delivery for All (BESDA) programme, which focuses on returning out-of-school children to classrooms.

“Through these collaborations, thousands of children have been enrolled in non-formal education centres and later transitioned into mainstream schools, giving a new lease of life to communities once plagued by educational neglect”

A GRADUAL TRANSFORMATION

While the journey is far from over, early signs of progress are visible. Enrollment numbers are rising, parents are becoming more engaged, and teachers are regaining morale said Magaji

In Dange Shuni, the once-empty classrooms now buzz with the sound of recitations, songs, and laughter. The walls that once cracked with neglect now hold colourful charts and drawings made by pupils who, for the first time, are beginning to dream again.

For Magaji, whose son is now back in school, the transformation is deeply personal. “I took him back after seeing the changes, now he comes home neat, telling me about what he learned with pride. That alone gives me peace.”

THE ROAD AHEAD

Despite these gains, experts warn that sustaining the momentum will require consistent investment, community participation, and strong policy implementation.

To that effect, Nura Muhammad, an education expert and lecturer at the Shehu Shagari College of Education, stressed the importance of community ownership in sustaining the government’s education reforms.

He said that infrastructure alone can not solve the problem, he therefore advised active school-based management committees, trained teachers who are motivated, and regular monitoring to ensure resources are used effectively.

According to him, only then can the progress seen so far translate into lasting change.

“But for a state once synonymous with educational neglect, Sokoto’s ongoing reforms signal a shift in both perception and practice. From abandoned buildings to bustling classrooms, the narrative is changing for a good “

As the morning bell rings in Dange Shuni, little voices rise in unison to recite the national pledge. For them, the future no longer feels out of reach.