Offspring Of Blood: Investigating Benue’s Herder-Farmer’s Clashes — (Part 2)

In this concluding part of the investigation, NNEOMA BENSON seeks to unravel the identities and agenda of the perpetrators of the Herder-Farmer’s crisis in Benue State while exploring the various narratives surrounding the conflict. The report, which documents the plights of victims, is also a fact-checking of allegations of religious undertone to the crisis. You can read the first part of the story here.

“They are rarely masked, invading villages in black hoods and trousers or army camouflage with crossbody bags. They have a striking resemblance, wielding dangerous weapons as they skulk about grown bushes. Only those lucky to flee their farms and communities live to tell the story.”

Advertisement

Musa Adamu, a Fulani herder now residing in Kiana, Nasarawa state, was born and bred in Epam, Guma LGA of Benue. As a pastoralist with nomadic parents, Benue continued to be the grazing field for their cattle until May 2017 when the Benue State Government under former governor, Samuel Ortom, enacted the Anti-Open Grazing Bill.

Adamu, along with hundreds of indigenous and non-indigenous pastoralists in Benue suddenly found themselves looking for an exit out of the state. The Livestock and Community Volunteer Guards (LCVG) set up to enforce the law were said to be ferocious in the execution of their mandate.

Ortom’s administration had established the LCVG to complement the local vigilante groups and the conventional security agencies to curtail the herder-farmer conflict in the state.

Advertisement

The Open Grazing Prohibition and Ranches Establishment Law, 2017 was a response to the rising tension and cycle of attacks over land, resulting in the deaths of thousands, and the destruction of farms and houses.

Did Anti-Grazing Law Stop The Conflict?

The law took effect on November 1, 2017, amidst apprehension over its workability in a state where itinerant herders had operated for decades.

Section 3 of the Anti-Open Grazing Law, demands that the legislation target six elements including:

(a) preventing the destruction of crops, settlements and property by open rearing and grazing of livestock; (b) preventing clashes between Nomadic livestock herders and crop farmers and (c) protecting the environment from degradation and pollution caused by open rearing and overgrazing of livestock;

Advertisement

Others include (d) optimising the use of land resources in the face of overstretched land and increasing population; and (e) preventing, controlling and managing the spread of diseases as well as easing the implementation of policies and enhancing the production of high-quality and healthy livestock for local, and international markets;

The law also made provision for (f) creating a conducive environment for large-scale crop production.

Conditions for the revocation of leases granted for the establishment of ranches are stipulated in section 11(2) of the Anti-open Grazing Law to be:

(a) Breach of state peace; (b) Interest of peace (c) Breach of any term or condition of the leasehold; or (d) Overriding public interest as stipulated in the Land Use Act 16.

The pastoralists condemned the law for allegedly violating their rights to freedom of movement and moveable properties.

This prompted a proposition by the Federal Government to establish colonies or Rural Grazing Area (RUGA) settlements in some states of the Federation, which was challenged by the Benue government in Court.

Advertisement

The Benue government refused to withdraw the law and went ahead to gazette it.

Data compiled by the Benue State Emergency Management Agency (BSEMA) showed the law may have done little or nothing to stem the herders-farmers’ conflict in the state.

There have been at least 105 incidents of farmer-herder crisis since 2019, and nearly 6,000 people have been killed since the law was enacted. Between 2015 and March 2023, no fewer than 5,138 people have been killed.

This is a huge contrast to the situation before the law. In the two years before the law (2015 and 2016) only a total of 1,986 people were consumed by the recurrent violence. In 2015, fatalities were 1,177 while in 2016, an estimated 809 were killed.

Although the state recorded 43 deaths in 2017 when the law was enacted, the number of deaths increased again the following year (2018) by 923.26 per cent when 440 were killed.

By 2019, the state again witnessed a 60.45 per cent decline in fatalities as a total of 174 persons were killed. Deaths decreased further by 49.42 per cent, in 2020 when an estimated 88 people were killed.

However, by 2021, the situation took a sharp turn as no fewer than 2,131 persons died following herder-farmer-related incidents. That year, the state witnessed a 2,321.59 per cent increase from the previous year.

However, in 2022, the fatalities again declined by 91.93 per cent as 172 per were reportedly killed.

As of March this year, no fewer than 104 had been killed.

Reactions

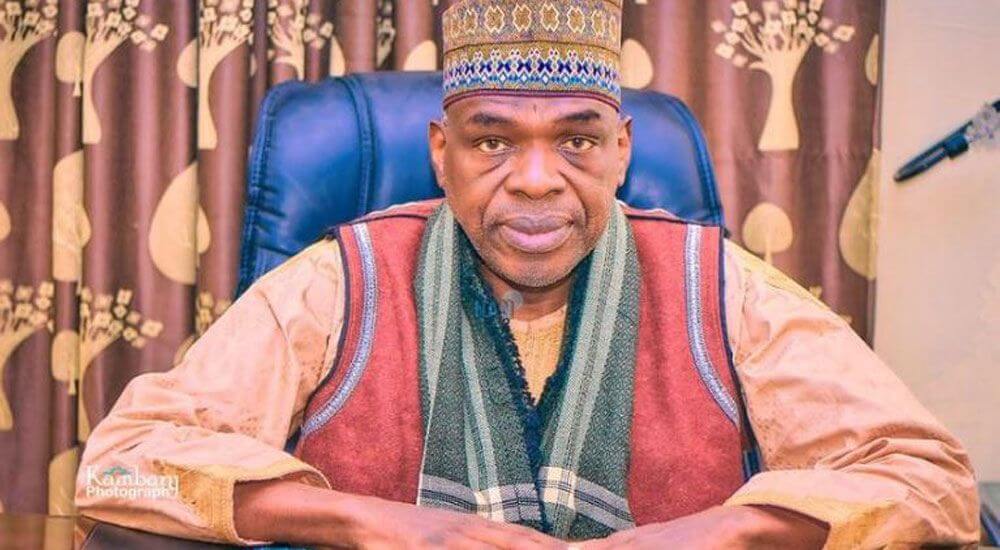

Usman Ngelzarma, the National President of the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria (MACBAN), described the law as “a total failure”, adding, “Ortom said the law will be a win-win, but it is a lose-lose for both the herders and the farmers. No one has benefitted from the law”.

He said, “Laws in a society are supposed to bring peace, but how much peace has that law brought to Benue?” Ngelzarma said, accusing the Ortom administration of politicising the security situation. He said the former administration enacted the law without giving pastoralists ample time to adjust.

Section 4 of the law prohibits open rearing or breeding of animals as it frowns at the movement of livestock on foot.

It demands that Livestock shall only be transported by means of automobile or locomotives from one destination to another in the state through rail, wagon, truck or pick-up wagons.

The law said, “Anyone who trespasses this section of the law shall be guilty of an offence punishable by one-year imprisonment or a fine of N500,000 or both (for a first-time offender) or three years imprisonment of N1 million or both for offenders.”

Owners of animals impounded will also pay N50,000, N10,000, N5000 and N1000 per cow, sheep, goat and poultry. The longer the impounded animal stayed in custody, the higher the fine.

The law further demands that potential ranchers submit, in writing, an application alongside the consent of the owner of the land to be used for ranching to the Benue State Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources department, acting under the Ministry’s Commissioner.

Within 30 days, the authorities “Will issue a ranching permit to the rancher alongside regulations for fencing and other activities in accordance with this Law,” valid for only one year.

The rancher must go through another application process to continue running.

The law, however, allows Benue indigenes to set up personal ranches, but the pastoralists insisted that yearly land renewal is not feasible.

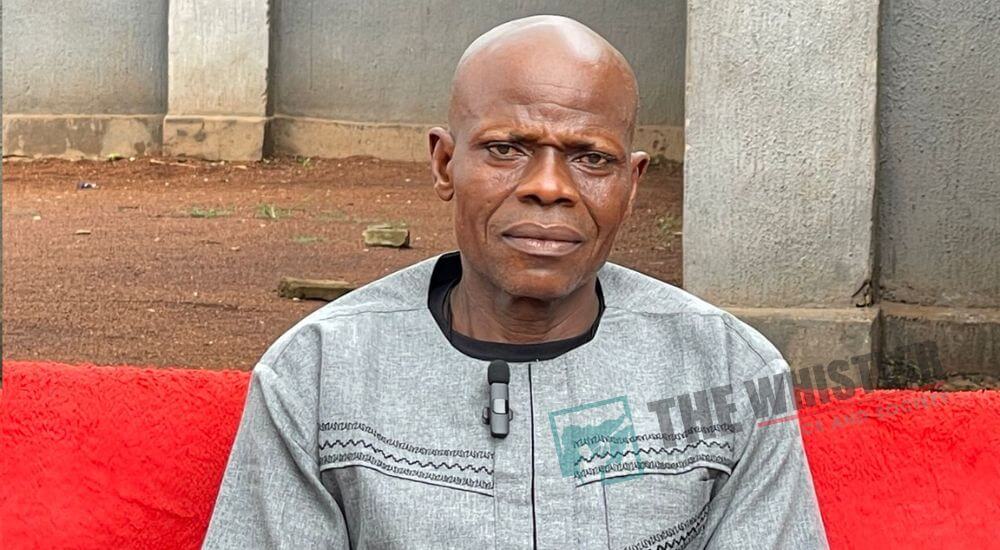

Reacting to the claims by the pastoralists, David Ogbole, a campaigner against the farmer-herder conflict, exonerated the state government from any blame. He said the government allowed six months for pastoralists to evaluate the bill and submit their grievances, “but none of them came forward to take advantage of the opportunity, instead, they challenged the law in court.

“Cattle rearing is a private business, not a government-subsidised venture,” he said.

No Longer Food Basket?

With over 80 per cent of its estimated 6.77 million population engaged in farming, the state remains one of the top five states with the highest levels of insecurity, despite both groups disagreeing over legal strategies to curb the crisis.

Insecurity has driven over 2,000 farmers out of their ancestral homes to Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) Camps in the Tiv-speaking areas of the state, while those in the Idoma and Egede-speaking areas take refuge in host communities, limiting farming activities.

Locals are concerned that the state’s status as the ‘Food Basket of Nigeria’ could be affected due to the high levels of insecurity. With 95 per cent of the state’s arable land capable of growing almost all tropical crops, Benue is responsible for at least 10 per cent of the nation’s food supply.

Philip Itodo, a farmer from Apa LGA, said he formerly harvested 800 tubers of yam yearly from his farm until April this year when suspected Fulani herders attacked his village. The attack took the lives of 13 farmers. Now, he was unsure if he could harvest up to 600 tubers of yam.

Itodo said he could not invest in his farm this year because he used money from his farm produce in 2022 to sustain himself during the crisis when they had to abandon farming for two months. As of August, Itodo said he could not go to his farm to take out his yam seeds for fear of being killed.

Oluma Benjamin, a civil servant from the Ochumekwu community of Apa LGA, cultivates yam to augment his income. He usually harvests at least 1000 yam tubers yearly. But he has been unable to sell this year “because of the attacks by herders.” Like Itodo, Benjamin decried the challenges encountered by farmers in the community due to the crisis.

As of August, many farmers still could not go to their farms to plant new seedlings for the due season. Farmers salvaged their seedlings using tricycles to convey them from distant farmlands for safety.

A single drop costs N12,000 ($14.7), and those with hectares of farmlands spend at least N100,000 ($122.6) transporting the seedlings in batches. The official exchange rate is N815.32 per dollar.

“The effect is devastating, and Food insecurity has increased,” the Chairman, All Farmers Association of Nigeria (AFAN), Benue State Branch, Aondongu Saaku, said.

Highlighting the effect on the state, he said, “In Gwer West, eight council wards have been deserted. No one goes there to farm. In Guma LGA, about seven wards out of 10 wards have been deserted;

“In Logo, three out of 10 council wards have been deserted; In Katsina-Ala, three council wards have been occupied by herders till now, Kwande has 15 council wards, and 12 have completely been deserted.”

Saaku noted that food crops in such places had yet to be cultivated, contributing to hunger and pressure on host communities while social vices among women and girls have increased. “People who hitherto would have been working on their farms to get money have now been rendered homeless,” he said.

The food basket now appears to be getting empty. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), about 25.3 million people in Nigeria will experience acute food insecurity in the 2023 lean season. Undoubtedly, the crisis in Benue is part of the reasons.

Conflict Leading To More Out-Of-School Children

Beyond food production, the security situation in the country has also led to a significant increase in out-of-school children in Benue State. The state had 10,000 out-of-school children in 2013 but has over 200,000 as of March 2023.

Such an upsurge in Benue alone contributes to approximately 13 million out-of-school children in Nigeria. According to the United Nations Children’s Funds (UNICEF), one in every five of the world’s out-of-school children is in Nigeria.

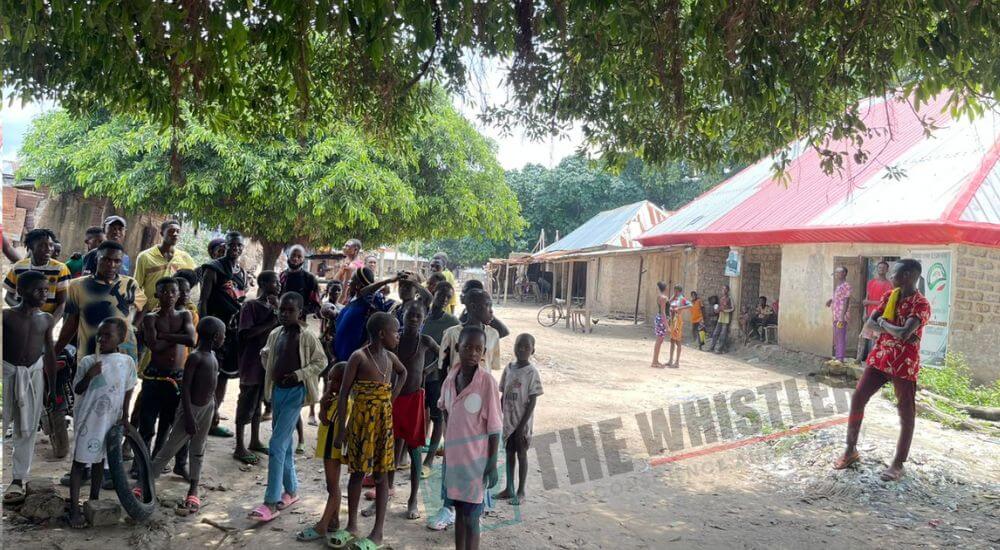

Findings by THE WHISTLER showed that children of learning ages have not attended schools in some LGAs, especially in Agatu, due to insecurity.

In Apa LGA, the number of students in classrooms is declining. Patrick Ochukwu, a teacher from the Akpete community in Apa LGA, said there’s a 90 per cent decrease in school enrolment 一 From 600 in January 2023 to less than 100 by August 2023.

The teacher’s last engagement with the students was in April when herders invaded the LGA. By August, only a few parents would let their children attend schools because of the likelihood of a sudden armed invasion.

In Agatu LGA, schools are barely functional. These schools’ sight suggests they had long been used for learning activities. THE WHISTLER observed that elementary schools in Okokolo and Aila communities were torched during the circle of attacks in the area.

Many parents who spoke to this reporter said the situation was undesirable as the insecurity was affecting the future of their children.

The immediate past government of the state had admitted to the frail education system, leading to a significant drop in enrolment into the state’s Universal Basic Education Board.

Margaret Onuh, a retiree in Apa LGA, diagnosed a scary future for education and the people of the state when she spoke with THE WHISTLER. She said, “In the next ten years, we will not have graduates, independent adults and those who will be useful to society. We will have more thugs, and people won’t be able to move freely in society.”

As it is, Benue may be among Nigerian states that may not meet Sustainable Development Goal 4 which targets that by 2030, all girls and boys should have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education.

Conflict Over Land Or Religious War?

The conflict between farmers and pastoralists who are predominantly Muslims has given a religious colouration to the crisis. Benue is a predominantly Christian state.

Christians have accused the pastoralists of plots to Islamise the state and to take over their lands while describing the excuse of climate change as a plot to achieve alleged “jihadist” objectives.

The religious leaders in Benue have been involved in the crisis, visiting attacked communities, consoling bereaved families, setting up IDPs for temporary safety, providing relief materials and gathering data on the victims.

A 2022 data by the Catholic Diocese in Makurdi said over 319 Christians were killed, 45 kidnapped, 234 injured and 16 raped in seven LGAs of Guma, Makurdi, Logo, Ukum, Gwer West, Apa and Agatu.

Videos and Pictures made available to THE WHISTLER by the church also showed how the attackers, largely suspected to be herders, invaded homes and schools used for IDPs. They sometimes killed and mutilated the bodies of children, women and men in some parts of the state.

Reverend Father Dennis Ujah, Priest of the Diocese of Otukpo, said the situation is “hydra-headed and multifaceted”, as the crisis between herders and farmers, specifically in Agatu LGA, connotes a “dimension of land grabbing.”

He said the attacks looked more like an attempt to dispossess the people of their land, while also giving the impression of a religious war.

Ujah said the insecurity has caused apprehension among Christians in the state who no longer feel safe attending church.

“The impressions will be that when they gather in their worship places, they become soft targets for assailants because those have happened in the past,” he said.

In March 2015, Christians in the Egba community of Agatu LGA were preparing for Sunday mass at about 5:30 a.m. when armed men attacked the church, killing at least 65 people. The building was not affected, but at least 35 people sustained injuries from bullet wounds, machetes, and houses.

Peter Aboje, a community leader in Okokolo, in Agatu LGA, where the first attack occurred in 2013, believed the crisis targets Christians because most attacks in his community were perpetrated on Sundays.

Caleb Adana, the head of the Okokolo Catholic Church, narrated how his father, alongside other church members, was killed in June 2019.

In May 2013, the attackers invaded the church and destroyed at least 50 of its chairs, altar attires and other materials. In 2016, during the mass invasion, the church also lost its priest’s residence — It was built in hopes that a priest would be sent there, but it was razed. To date, the church has yet to rebuild another.

By June 30, 2019, the attackers invaded his church during a 6 a.m. mass on Sunday. They came in black apparel, shooting sporadically in the air and eventually opening fire on the church members.

At least 25 people were subsequently confirmed dead, eight of whom were aged and sick and 13 were children. Only those who could escape lived to tell the story.

“Immediately they came, we ran to the hill. My dad is an old man; he could not run. They met him and killed him before he could escape,” Adana said.

Other churches burnt down in Agatu include Catholic Churches in Adagbo, Akwu, Ugboju, Deeper Life and Methodists, among others, many of which have been rebuilt.

According to Ujah, the easiest way to displace a people is to destroy their worship centres. “When you take away their religious place of worship from them, a sense of meaning is closed from their lives, and it is from that perspective that if you want to displace a people, get rid of their religious places, houses markets, and no one will stay at home because they would be scared that places where they could easily be gathered, would become areas of soft targets for aggressors.”

Reacting to the claim, Ngelzarma said, “They (herders) are not anywhere to take anybody’s land. The majority of them are just Muslims by name. They don’t even know the religion but they are concerned about their cows and their source of livelihood. So, if you go and kill a Fulani man, he will retaliate by killing everything you have whether houses or churches.”

When asked if these were the reasons for the burning of churches and houses in Agatu and other areas of the state, he responded, “Yes! We also have pictures of where pastoralists and their cows were killed. If you kill him and kill his cow, he will retaliate and damage all you have.”

He said the burning of churches was not a plot by the Fulani to Islamise the state. “Who are they to Islamise others? Most of them (herders) don’t know the Quran because they live in the forest. They don’t have Western education because of the nature of their business. How many mosques did they erect if they were talking about Islamisation?”

Catholic Church Laments Upsurge Of Displaced Christians

Since the 2001 massacre, when the Catholic Diocese in the state, with aid from international organisations, established IDPs in the Tiv-speaking areas, there has been a proliferation of displaced people that the government couldn’t resettle.

The Catholic church took up the responsibility and built IDP camps in the hope that after a while the displaced people would be returned to their ancestral homes. But that hasn’t happened yet, lamented Reverend Father Moses Iorapuu, Vica General, Makurdi Diocese, who added that the numbers have instead been growing.

The Catholic body shouldered the responsibility of the IDPs until the state government and other humanitarian organisations came along.

“Now, if we are talking about who is responsible for this exodus, the people who have been displaced are Tivs, and most of them are Christians, and a majority of them are Catholics.

“Today, millions have been displaced who cannot be resettled. I went back to the camp on the 20th anniversary, and I could still find people who had been there since 2001. You can imagine how many have been displaced across other LGAs. All have been attributed to Fulani herdsmen,” Iorapuu said,

Confirming his claims, a woman in the Ichwa IDP Camp, North Bank in Makurdi, told THE WHISTLER she had been at the camp since 2014 when “Fulani came to our village.” She added that her five children were born at the camp.

The living conditions in the camp are unpleasant. The people stay in makeshift tents numbering over 6000. As of August 12, a total of 14,229 people, including 6,231 (3,071 male and 3,106 female) children, 2,255 male and 5,743 female adults, were residents in the Ichwa IDP Camp, North Bank in Makurdi.

The over 7,998 children in the IDP camp who barely have access to school are largely from Christian parents who are also farmers.

This is why Iorapuu insisted that if the crisis has no religious undertone, “then we want to see these people go back and live their normal lives. We are tired of seeing people in the camps and tired of giving them handouts.

“They all have the right to live a normal life. The church has done its part and if they claim the problem is political, let there be a political solution. They need them to go back to their homes,”

But again, Ngelzarma disagreed, saying it’s a “mere coincidence” that the majority of the pastoralists are Fulani Muslims while the farmers are predominantly Christians.

The Benue Christian leaders may be justified in seeing the crisis from a religious dimension because of the high casualty figures recorded. But there’s no evidence to back the claim of a Jihadist plot beyond imaginative rationalisation of the conflict.

The Fulani may have suffered less casualty in terms of human lives largely because the pastoralists always had their families in faraway places while the attacks were perpetrated on Benue soil.

But Iorapuu expressed the minds of his people when he said, the pastoralists cannot continue to “sacrifice the lives of human beings because of animals”, adding, “Benue is not the only place that has fertile lands for their animals to graze.”

Analysts Share Opinions

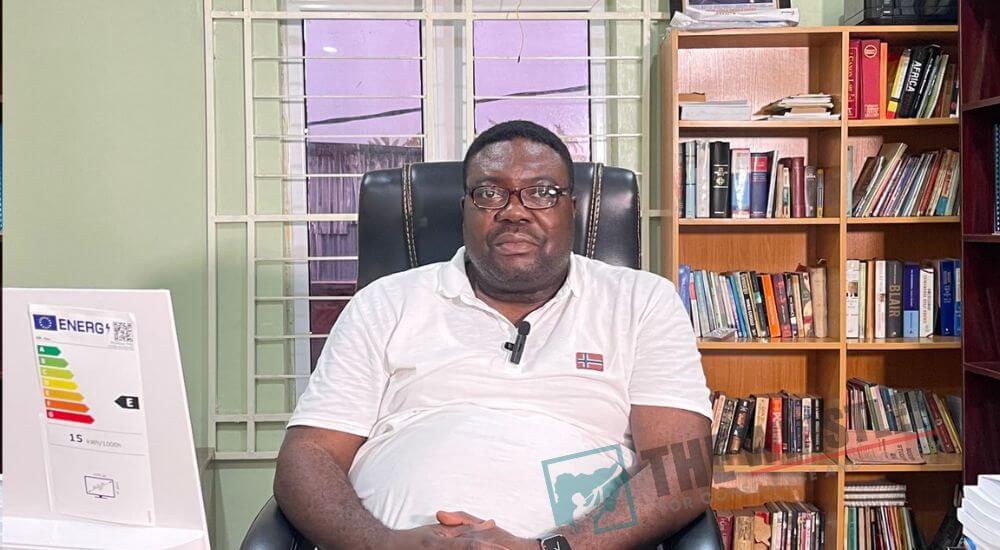

Confidence MacHarry, a geopolitical security analyst at SBM Intelligence told THE WHISTLER that it is easy for conflicts to take political, religious and ethnic colouration despite the competition for limited resources given the actors involved.

But Murtala Abdullahi, a researcher and climate change expert, told THE WHISTLER that the crisis was prolonged because it was politicised.

He said efforts by the Federal Government to address the problem were rejected for political reasons. He said the establishment of the National Livestock Transformation Plan (NLTP) and later RUGA were interpreted by the state government as a land grab and as a form of state-sanctioned ethnic cleansing in favour of the Fulani.

“To be honest, what Ortom did was simply to latch onto the politicisation that the Buhari administration already did with the crisis and decided to aggravate it further,” MacHarry noted.

The Benue Police Command also believes the proliferation of arms in the state has fueled the crisis. It has increased the level of banditry, and terrorism ravaging the state.

The state’s Police Public Relations Officer, SP Catherine Anene, told The WHISTLER that despite the law prohibiting open grazing, pastoralists refused to comply.

Anene said, “The farmers at some point get angry and take laws into their own hands by rustling cattle when herders graze on their farms. They seize them and take them away, and all of that creates tension. There are cases where herders come to report that their cattle were rustled while farmers come to complain that herders graze on their lands.

“Sometimes criminals among these two communities, conspire and steal these cattle, whether there is grazing or no grazing. When they steal, it fuels suspicion and herders will suspect farmers even when farmers did not do it, and that was causing a lot of trouble in the state, including killings and attacks, but it has been brought to the minimum”.

Despite the conflicts between the herders and farmers, Anene said, “The Benue people are also quick to get violent over land disputes, and the security agencies will have to move in to settle the matter between brothers. We try to manage the situation to bring in peace”.

Combatants’ Want Peace

In the convoluted and complex moving parts of the conflict in Benue State among herders and farmers, the combatants appear to dig deeper into their holes with no end in sight. But there is hope for a peaceful resolution as each side has put forward the conditions for peace.

The Benue State Chairman of the All Farmers Association of Nigeria (AFAN), Aondongu Saaku, said the farmers need assistance to move on with their lives.

“The farmers who have deserted their lands and are in other locations, are requesting assistance so they can carry on with their lives. The government is also unwilling to give us loans or initiate projects that farmers can be involved in to better their lives,” Saaku said.

He also pleaded that the government should create a safe space for women and men to cultivate on their farms without fear of being attacked.

On their part, the pastoralists are seeking the establishment of a committee consisting of the representatives of the pastoralists, farmers and other relevant stakeholders to oversee the activities of both parties in the state and the security situation for posterity.

Addressing the Benue Governor, Ngelzarma said, “We want the government to temper Justice with mercy. Review the law in a way that it will work in bringing peace and harmony into the society.

“All we want from him is Justice and fairness. Also, he engages the farmers and pastoralists at the local level from time to time, to ensure that he creates the necessary atmosphere of peace for the farmers to be able to go to their farms.”

Also, religious bodies in the state are demanding an end to the killings and the resettlement of the IDPs to their ancestral homes.

“We want the killings to stop. You don’t have to kill people to graze your cattle, there is enough grass everywhere,” Rev Fr Remigius Ihyula, Coordinator of the Foundation for Justice Development and Peace (FJDP).

The Church is also pleading with the federal and state governments to expedite a resettlement plan for IDPs that eliminates persons of threats from their ancestral homes to enable them to return.

MacHarry, a security expert, also recommends that the state government should consider encouraging pastoralists to settle into ranching.

“The government should provide provisional loans to pastoralists from the Bank of Agriculture that will enable pastoralists to buy the land from wherever they desire in the state to ranch their cattle.

“Also, the most logical conclusion to the issue could be ranching, because in 2023, there are no reasons cattle should be left roaming on the streets, on the highways, and on the roads, and into people’s farms,” MacHarry said.

There may be light at the end of the tunnel as the new administration in the state is determined to address the challenges and bring peace. Dr Edward Amali, Director of the Livestock Services, Ministry of Agriculture, Benue State, revealed that the state governor, Reverend Father Hyacinth Alia, is considering reviewing sections of the law the herdsmen consider unfriendly.

Amali said, “The new government has promised to review the law and try to see how far they can sort out areas of differences or not and see how they can engender peace. So we are waiting on the wings to get that rolling and to see how far we can go with that.

“Our people are not so happy because of the killings and the dispossession of the citizens of the states, and their land. There are areas in the state that are still occupied by the herdsmen and they won’t go away.”

He expressed hope that both parties would reach an agreement and that the conflicts between farmers and pastoralists be “quickly sorted” to enable the people to go back to their farms.

This story was produced with funding support from the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ) in partnership with Code for Africa.