Offspring Of Blood: Investigating Benue’s Herder-Farmer’s Clashes — (Part 1)

This investigation by NNEOMA BENSON seeks to unravel the identities and agenda of the perpetrators of the Herder-Farmers‘ crisis in Benue State while exploring the various narratives surrounding the conflict. The report, which documents the plights of victims, is also a fact-check of allegations of religious undertone to the crisis.

They are rarely masked, invading villages in black hoods and trousers or army camouflage with crossbody bags. They have a striking resemblance, wielding dangerous weapons as they skulk about grown bushes. Only those lucky enough to flee their farms and communities live to tell the story.

Advertisement

Augustine Ikwulono, 68, arrived from his farm at about 5 p.m. in April 2023. He was having an early supper outside the small open area of his residence in the Imana Ikobi community, Apa Local Government Area (LGA) of Benue State, when he heard the muddled footsteps of villagers. Everyone in his household, including his wife, fled, leaving him behind.

“Before I could reach that compound,” he said, pointing at the nearby building. “I met with them—the Fulani—the ones that met me wore Army camouflage, and they carried sophisticated weapons. They did not say anything to me but opened fire and shot me in my back while trying to escape.

“I couldn’t do anything but run into the bush with my back bleeding from the bullet wound. I climbed a hill and burst out on one side, where I met one Isah, who felt sorry for me and asked me to sit down. I told him no, I would go. So, he sent for a machine (motorcycle) to pick me up from under the hill to the hospital”, he said while recounting his escape to THE WHISTLER.

Advertisement

Ikwolono spent four days in a hospital in Agatu LGA, less than an hour’s drive from Apa, where doctors operated on him. He recovered and returned to his village to see his house razed and his farm proceeds, mostly yam, harvested and others carted away by the assailants.

Since then, his health has deteriorated, and he lacks the strength to provide for his family as he should. “Feeding is now a challenge”, he said, and the family’s daily consumption of processed cassava (also known as fufu) and palm fruit extract used for soup is past bearing.

Scorched Earth Attacks And Graves

At least 40 houses were razed in Imana Ikobi. Few villagers have renovated or rebuilt their homes, while some sleep on the bare ground after their mattresses are destroyed or carted away.

Advertisement

Oinu Matthew told THE WHISTLER that his extended families now cohabit and feed on the meagre produce from their farms. Other times, they depend on their neighbours for a meal. The father of six children from Imana Ikobi also had a near-death experience after assailants invaded the same community on February 27. He had escaped into the bush after hearing gunshots.

“I saw the men wearing black up and down with guns, and they pursued me into the bush. I saw their faces. They looked like Fulani men,” he said, adding, “Unfortunately, I told one of my brothers who was at home to leave the house while I was running away. When I could cross the community through the bush, I called my brother’s phone, and a Fulani man picked it up.”

The Fulani man told him his group had killed his brother and asked him to come and pick up his corpse! “That day, they killed five men. They burnt our houses, destroyed our assets and stole our properties. They started living in our houses permanently. They cooked our chickens, and they left nothing behind for us.”

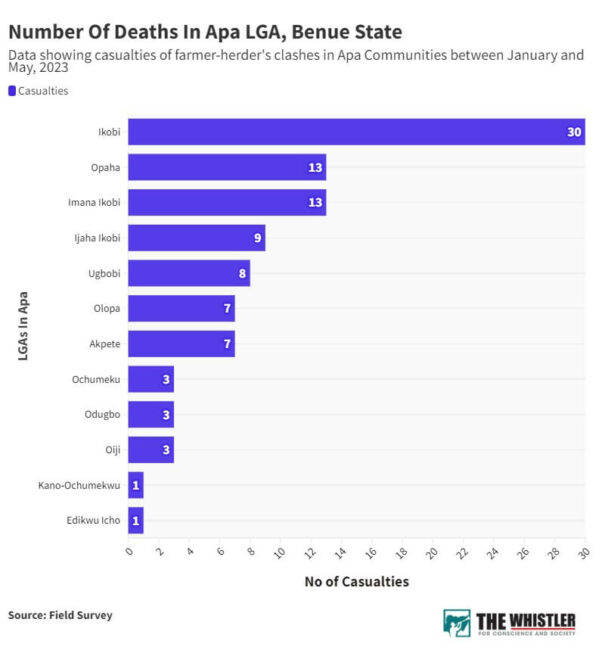

Data from various leaders of the Apa LGA showed that at least 98 men were killed between January and May 2023, and (12) communities were also affected within the period under review.

A breakdown of the data showed that 13 men were killed in Imana Ikobi in separate attacks. In April, 13) were killed in Opaha, including (2) army officers, (8) in Ugbobi and (3) in Oiji. In March, (3) were killed in Odugbo and (1) in Edikwu Icho.

Advertisement

In May, (7) were killed in Akpete, (7) in Olopa and (3) in Ochumeku. In February, (1) was killed in Kano-Ochumekwu, (30) in Ikobi and (9) in Ijaha Ikobi within the period in review.

Samuel Enokola, a traditional leader of the Ugbobi community, explained that the herders do not touch women when they attack a village. They kill only the men whom they regard as threats to their existence.

So, when these attacks occur, residents flee to Ugbokpo, where they squat with relatives after an attack because there are no Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) camps in Idoma lands. During the day, they would journey for at least two hours on foot to their villages and farms. The people suffer in the aftermath of such attacks.

Women Here Are Brave

Like Ugbokpo, Obagaji is a haven for displaced communities in the Agatu LGA. The suburb is the headquarters of Agatu, another worst-hit area among the Idoma-speaking tribe. Agatu is bound to Apa by the North, and the proximity makes both axes danger zones.

A drive over a 74-kilometre distance, across over ten communities in Agatu, showed that the villagers are yet to recover from the mass invasion of the Fulani herders between 2013 and 2016 and other pockets of attacks in subsequent years.

Ologba, a community after Obagaji, is deserted, and no human lives there. The razed buildings are dressed with branches from aged trees, and the locals are now refugees in Obagaji while others moved to Otukpo LGA, bound to Agatu by the South.

Data obtained from the LGA officials by THE WHISTLER showed that the Fulani between 2013- 2016 affected 15 communities, razed over 700 houses, displaced over 1000 women and children and killed over 368 people.

Between 2019 and mid-2023, at least 105 incidents of farmers-herders crisis were recorded; over 1,500 people were reportedly killed, and over 1.5 million people were displaced in the state.

Moving through the Agatu hinterlands, talking to dozens of people across the affected communities revealed that fear of death from an attack by locals or suspected herders is palpable.

Women, the most vulnerable victims, are raped, injured or widowed. They are attacked by both herders and local criminals.

“Some women are raped by herders and abandoned on their farms. Not many survive; those who do will take two or three days before we find them,” a community leader of Okokolo, Anthony Aboje, said.

On March 13, Oteni and her husband were en route to their farm on a motorcycle when herders intercepted them.

Speaking in Idoma, she said, “I was going to Ogboji on a market day when two Fulani men attacked me. They met me at Odugbeho. They asked us to give them our motorcycle, and we refused. Then, they beat us and cut my hand with their sharp machete. They collected our motorcycle, and we have yet to see it”.

Rebecca Micheal, with ten children from Agatu LGA, said they are constantly faced with armed herders skulking about the bushes, chasing them away from their farmlands.

“I was on my farm with other women in July when I saw the bush moving. Then we knew they were coming. They were carrying guns and chased us away from our farms,” Micheal said, noting the difficulty maintaining previous outputs of farm produce.

Mary Emmanuel, 26, whose portions of lands are now inaccessible due to recurring attacks from herders, said, “If I go to the farm alone, they will kill me.” She currently farms on a small portion near her house.

The descriptions of the villagers here are peculiar. Both men and women would rather forsake their farms than get killed when herders invade their farmlands, and for most women, walking in groups prevents the attackers from harming them.

The Victims Are Also Aggressors

The once peaceful farming and fishing environment of Agatu has lost its innocence. According to John Ikwulono, former Vice Chairman of Agatu LG Council, “Agatu has become a place where people are restless, undergoing pains and challenges as a result of both internal and external crises. Internal crisis because we have a communal crisis that has affected some communities in Agatu.”

Aside from the herders and farmers conflict, Benue communities also suffer intra-communal crises on the sideline. It is barely acknowledged or given attention. Most villagers are afraid to speak of the internal killings and kidnappings recorded across the LGA, and to those outside the state, every incident is perpetrated by Fulani herders.

David Ogbole, Co-convener of Movement Against Fulani Occupation, described the situation as one of the components of insecurity in the state where a community or a clan within a community clashes over farmland, fishponds and chieftaincy issues.

Elizabeth Inalegwu, 35, was sighted in the Aila community on one of her farms. The mother of five is stuck with the farm in Aila and has involuntarily neglected the farm in Egba for fear of being killed. Now, she is left with little produce for harvest by 2024.

“In our heap farm, we cannot go there now because of the Egba people coming to attack us. We have now left that side between Ogbaulu, Aila and Odugbeho. Our property is still on that farm because we planted Guinea corn and Iron beans after Fulani removed our yam. Even to go there and spread chemicals or cut the grass, we cannot go because of the Egba people,” she said.

Amos Odoba, an opinion leader of the deserted Ologba, explained that there had been an ongoing conflict between Egba and Ologba over an ancestral fish pond beyond the invasion of Fulani herders in his community.

He said, “The Ologba and the Egba have been fishing together, but the disagreement came like a joke over a fish pond. The military tried to make peace, but it failed. Then, they started to kidnap and kill people”.

He recalled what led to the issue, saying, “But there was a survey carried out by a Federal government unit. They told us that the fish pond is suspected to have crude oil, so many big men from that place (Egba) wanted to take over the fish pond so that they can use it for themselves, and that has been the genesis”.

The Fight Over Land

The age-long conflict between farmers and herders remains a catalyst for the numerous deaths and displacements recorded across Idoma, Tiv and other minority-speaking tribes.

But history says the Fulanis and Benue people coexisted peacefully in their communities until recently. The presence of the Fulanis, their families and cattle from November to March was mutually beneficial to the people.

The fertile grasses in Benue made the cows of the pastoralists grow fatter and healthier, while the cow dung fertilised the soil for farmers.

The Benue indigenes bought chickens, Main-Shanu and Nono (cow milk extraction) from the Fulani, while the community reciprocated by selling various kinds of grains. As a result, some local government areas such as Ogbadebo LGA have naturalised Fulani bearing Idoma names.

Ogbole explained that the Fulani had a pass-ritual: “They come after the harvest seasons in November to eat the post-harvest wastes beside the farmlands.

“By the time the rains begin in April, they quickly return to the North, where the grasses are grown for grazing and to avoid the river volume getting too high for their cows to cross. So, they cross while the rivers are still dry in April.”

The Fulani made Benue their home, given the limited resources in Northern Nigeria. Most pastoralists took abode in LGAs like Guma and Logo by the Benue Valley for easy access to water.

The year-round river accommodates at least 200,000 cattle yearly, encouraging an influx of herders and cattle in Guma, Agatu and Gwer-West LGAs. So, what changed?

Ogbole, in his book: ‘Herdsmen Crisis in Nigeria: The Benue Peace Option’, claimed that “By 2001, a Tiv farmer named Umande found a Fulani man grazing his cow on his farm and crops.

“When he accosted the Fulani man, the herder drew out his sword and killed him. That was the first offspring of blood in that relationship between herders and farmers.”

The situation degenerated, with the Benue locals vowing not to accommodate the herders in their communities.

The pastoralists would then avoid hostile areas for fear of being attacked, yet the encroachment continued, as did reports of killings on both sides and the rustling of cows.

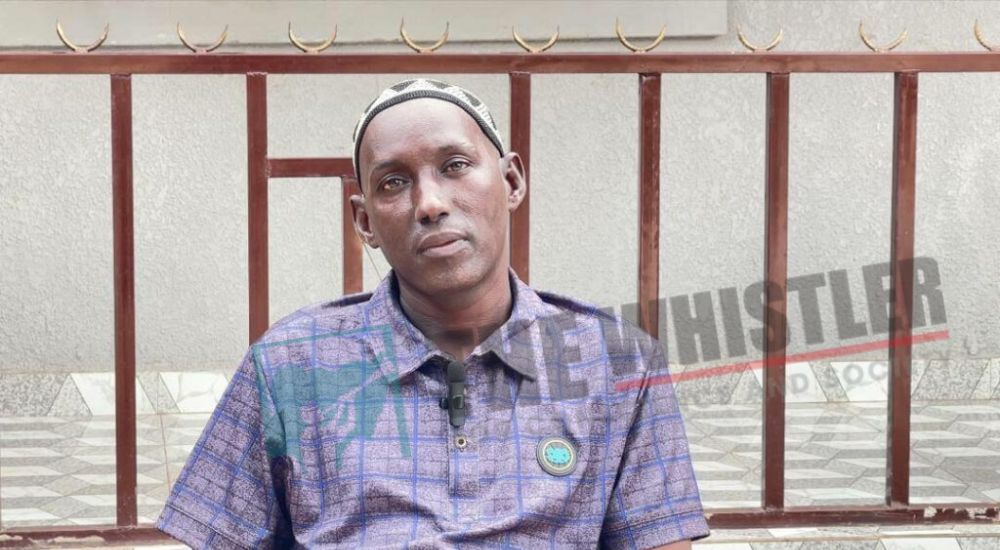

Traditional rulers on both sides prevailed over the recurring disputes, and “for every encroachment on the Benue man’s farm, the pastoralists are asked to pay a fine, often outrageous,” Baba Ngelzarma, National President, Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association (MACBAN), told THE WHISTLER.

Giving a background of the crisis, Benue-born Ibrahim Galma, State Secretary of MACBAN, explained how climate change also exacerbates the conflict over land.

He said, “Due to factors including desertification, lack of greener pastures during agricultural development, population growth, and many grazing areas in Nasarawa and Plateau States becoming farming areas, the only saving grace for the herders became the riverine of Benue due to its year-round water because cattle cannot survive without water.

“The Benue River passing through the state became a competitive area for the herders, who concentrated their grazing in Agatu and Gwer West. Due to their increase, farmers who used to farm around the river bank started to have problems with the Fulanis for trespassing into their farmlands.”

When the Benue locals attacked them for trespass, the Fulanis complained to the kindred heads in the state, whom they believed would intervene and settle the disputes.

“But things changed in 2014 when more sophisticated weapons were used to attack our cattle. Many cattle were killed in Agasha and along the riverine areas, including 17 herders.

“We do not know how they got the weapon because those people are criminals. This triggered the crisis in Guma, Logo LGAs, and some parts of the Makurdi metropolis, and the herders retaliated. So, it became more complex, and many lives were lost,” Galma narrated.

The alleged Agatu criminals would later kill a Fulani leader, Ardo Mama, and attack pastoralists and their cattle in the riverine areas of the LGA, and there would be a departure of the Fulani in preparation for the invasion of Agatu where thousands were displaced and hundreds killed.

According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), “Approximately two-thirds of the labour force makes a living through farming or pastoralism.

“With minimal irrigated land, both activities rely heavily on seasonal rainfall and related weather patterns, so the effects of climate change can be intense.”

Global warming has also increased the severity of droughts and contributed to extreme seasonal variability in water supply across the Sahel and neighbouring countries.

These long-term climatic trends disrupt and harm traditional livelihoods like farming and herding, increasing economic uncertainty.

Analysing the situation, Murtala Abdullahi, a climate and environmental analyst, said that Nigeria has at least 11 states in the North battling with factors exacerbating climate change.

These factors include the felling of trees and increased use of firewood, which expose the soil and expand desertification in such areas.

The effect, Abdullahi said, “Increases the scarcity of these lands, and for pastoralists, there is going to be conflict over land with farmers competing for more resources with pastoralists.”

The crisis between farmer-herders has become a significant security problem, leading to the death and displacement of thousands of Nigerians, while climate change has aggravated the conflict.

The reality far outnumbers reported incidents as each dry season reminds the Benue farmer of his loss and impending tragedy — his inability to sleep without trepidation, educate his child, access health care, and cultivate on his farmland, among others, owing to seasonal infiltration of pastoralists.

Fulanis Are Victims Too

The consequences are evident, as many pastoralists who spoke to THE WHISTLER during this investigation said they were innocent of the crimes attributed to them but admitted to the existence of criminals on both sides, perpetuating attacks and fueling the crisis.

“The Benue people use firearms to attack herders, and they acquire them indiscriminately, and herders find ways to protect themselves.

“In Benue, it has become a habit to find youths with firearms, and we regard them as criminals; even the herders found with firearms, we call them criminals. We also accuse them because we have seen those victimised with bullets. We also have Fulani attacked with bullets, confirmed by the police.”

While the Benue farmers have accused the herders of plotting to takeover their land by killing the locals and destroying their properties, the pastoralists said they had recorded many cattle rustling, theft and killings by Benue militants.

However, both Ogbole, an indigene of Otukpo LGA in Benue and Ngelzarma, from Yobe, Adamawa State, had different stance on the issue of cattle rustling but agreed that there were criminal elements among herders and the Benue residents.

According to Ogbole, cattle theft differs from cattle rustling: “People who rustle cattle don’t rustle for the meat, but for the cargo they carry, including contraband drugs, hard currency, and arms.

“Once a rustler sees a herd of cattle, he knows who it belongs to and what cargo it carries.” But Ngelzarma faulted the claim, saying, “That is a blatant lie” because cattle rustling demands an in-depth knowledge of the art of herding, including the ability to command the cattle’s attention enough to separate the cattle from the general herd.

Findings indicate that the farmers and herders in Benue bear the brunt of cattle rustling and the general crisis among the ethnic groups.

Respondents on the conflict confirmed to THE WHISTLER that criminal elements among Benue people connive with Fulani criminals to rustle herds of cattle, fueling mutual suspicion that triggers violence. Usually, the actual perpetrators are never punished; only innocent residents become victims.

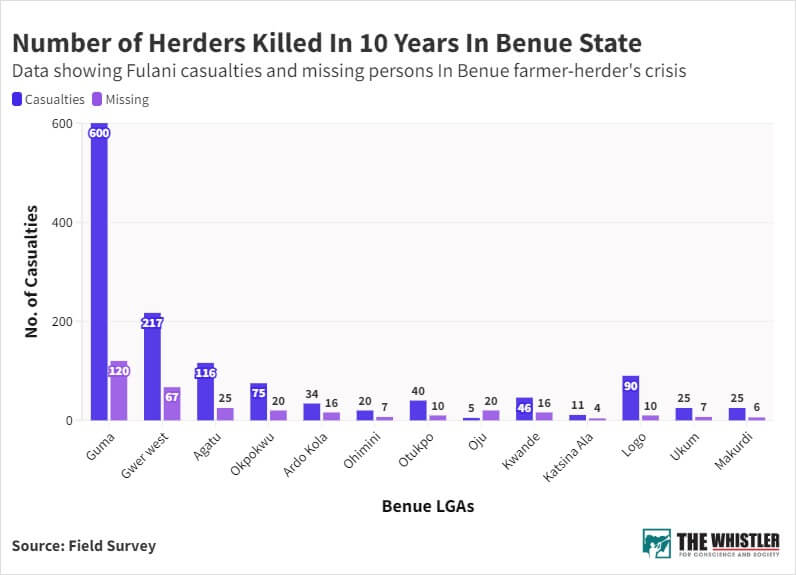

Data obtained and analysed by THE WHISTLER showed that 1,304 herders were killed in 13 Benue LGAs between 2013 till date. The numbers may be more, but the whereabouts of at least 328 are still unknown.

Ngelzerma shared a telling experience. He said, “There was a time when the Benue people went on a rampage, killing the herders and their cattle, and when they came for reprisal, they didn’t care who you were or what you had.

“If you think that what they have in the forests are just huts and you destroy and kill them, the same people you see with the cattle will also come and burn your houses.

“And these people are not militias. They are the same Fulani herders; the Benue farmers kill their cattle and wives, and we have pictures where they were brutally killed. So, if you kill his cow, he will also damage all you have. It is a tooth for a tooth thing,”

Videos seen by THE WHISTLER showed how herders mutilated the corpses of residents in the Tiv-speaking areas around the Makurdi axis after killing them.

It was likely retaliation for the killing of Fulani cattle, as pictures made available by the herders showed at least 117 cattle slain by suspected Benue locals in December 2022.

All efforts to visit the affected communities in the Tiv-speaking area failed due to severe insecurity.

It was also challenging to find a Fulani herder in Benue State to speak to because they had been “chased out” of their settlements by the locals. They now reside in Nasarawa communities bordering Benue State.

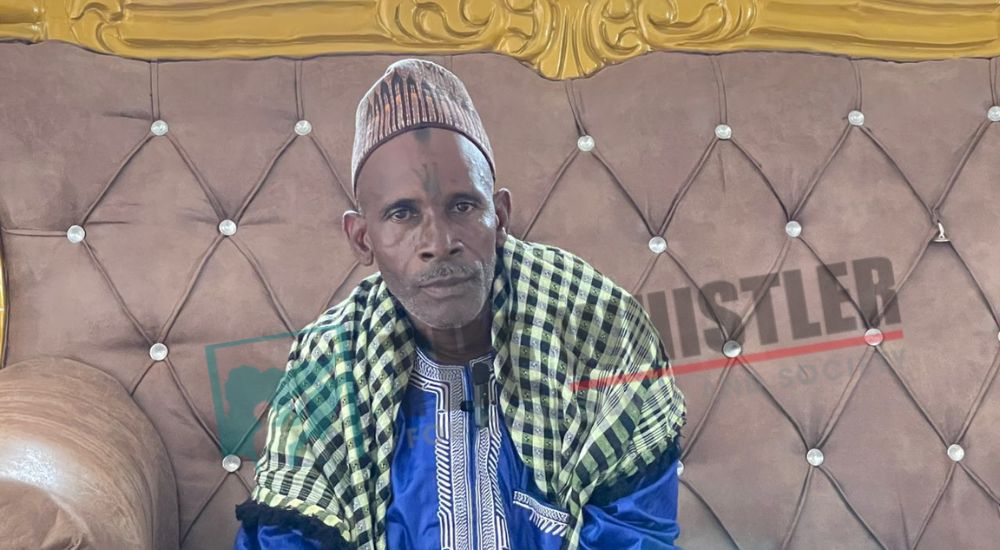

Ardo Muhammed Madaki, Emir of Kadarko Giza development area in the Keana LGA of Nasarawa bordering Benue State, told THE WHISTLER he was “chased out by former Benue State Governor, Samuel Ortom” following the Open Grazing Prohibition and Ranches Establishment Law 2017.

The law was a response to the rising tensions and cycle of attacks, resulting in the deaths of thousands, the destruction of farm products and houses, cattle rustling, and the disruption of peace and orderliness in the State.

It was aimed to prevent clashes between nomadic livestock herders and crop farmers, among others.

But the Fulani have alleged that the Livestock and Community Volunteer Guards (LCVG) set up by the immediate past Governor of the State, Samuel Ortom, to ensure compliance with the law prohibiting the open grazing of cattle in the state are being used to exploit them.

The herders accused the Guards of exploiting the outfit by deliberately chasing the cattle into neighbouring Tiv communities to confiscate them for ransom.

Before the law was enacted, Emir Madaki said he lived in the Guma LGA of Benue with his family, where he went about his herding business unperturbed despite the crisis.

“Honestly, I have been managing since I left Benue State. Grazing my cattle has also been difficult because if I cross the boundary into Benue State, the Livestock Guards will shoot and kill my cattle.

“Since last year, the Guards would enter Nasarawa and chase our cattle into Benue so that we could pay a ransom. If you have many herds of cattle and the Guards chase you into Benue State…

“They could demand N30 million to release the cattle, and we pay the money to Linus, a Tiv man in charge of the Livestock Guards.”

Alhaji Jaile Madaki Doma from Akpata LGA, Nasarawa, also narrated his ordeal in the hands of the Tiv people. His community borders the Tiv-speaking area of Benue. His experience with Tiv criminals and the Livestock and Community Volunteer Guards (LCVG) is unpleasant. Speaking to THE WHISTLER, he said in Fulani language:

“The people that came into our community came to kill our people. I cannot remember what they were wearing, but the government officials came and arrested more than 600 of our cattle and asked us to pay over N20 million.”

According to MACBAN, a total of 27,000 livestock have been killed and rustled in the last 10 years, while the immediate past administration of the state auctioned at least 1000. “We have paid over N400 million ransom to get our cattle confiscated by the Livestock Guards since 2018 to date,” MACBAN said.

The Fulani herders accused the immediate past administration of Benue State of complicity in the farmers-herders crisis. “Often, the Livestock guards never return the cattle in the same number they were seized,” Ngelzerma said.

To a Fulani man, his cattle are his pride, and he will do everything to nurture them until they are mature for commercial purposes, used for marriage settlements and dowry for his female children.

The herders said a cow is worth at least N600,000 and a similar tragedy will happen to those who kill their cattle or herders.

“In the Northern region, the Fulani do not have lands. They stay in the Forest. They don’t lay claim in those areas because, whenever development comes, they move away from that area. Their main concern is where their cattle will find grass, and they don’t care about the land. They are there to take nobody’s land,” Ngelzarma said.

In the convoluted and complex moving parts of the conflict in Benue State, the herders-farmers’ crisis has turned into a theatre of war, where the combatants dig deeper and deeper into their holes with no end in sight.

This story was produced with funding support from the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ) in partnership with Code for Africa.